By Localiiz

Branded | 17 May 2024

By Localiiz

Branded | 14 May 2024

Copyright © 2025 LOCALIIZ | All rights reserved

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to get our top stories delivered straight to your inbox.

Header images courtesy of Noah Buscher (via Unsplash)

A chill creeps in through the window cracks. The lights in the room begin to flicker. You hear the doorknob turn, clutch tight the wooden stake in hand, and whirl around to face… a Chinese vampire decked out in full Qing dynasty attire? Does a wooden stake still work? Do you turn a weapon against Transylvanian vampires on a local with blood-sucking inclinations? As the Chinese have discovered our ghosts and monsters through the centuries, so have we teased out little by little—from folklore and religious practices—their unique fears and the ways in which they might be dealt with. This Halloween, learn about nine traditional Chinese essentials that are sure to chase unwanted creepy visitors off your doorstep.

Roosters atop temple altars, roosters at ceremonies, roosters on New Year paintings… Wherever the Chinese pray for good luck, there is oft the familiar feathered figure. Traditionally, the chicken has been considered a symbol of fortune because its name jī (雞) is pronounced like jí (吉), the word for auspice. Roosters in particular—their proud red combs and brilliant coats reminiscent of the mythical phoenix fènghuáng (鳳凰)—are invoked even in mere image form as an effective ward against evil.

That roosters tell the coming of dawn makes their cries powerful in folk belief. According to Chinese cosmology, yin (darkness) and yang (light) are opposing forces. While ghosts and monsters aplenty belong to the former, the sun and the rooster, by association, are of the latter—meaning the beings, which from shadows come, have a natural affinity for the night and an innate terror of the day. Roosters are thus as harbingers of doom to these creatures, each of their cries a signal for flight. In the classic What the Master Would Not Discuss (子不語; Zǐ Bù Yǔ), there exists a specific record of ghosts shrinking by a foot at the first cry, another foot at the second, until they eventually disappear completely into the ground, and where Chinese vampires fall motionless. If ever you run into a malicious supernatural being, imitating the cry of a rooster just might keep you safe.

As roosters are ghosts and monsters’ natural enemies for beings of yang, so are dogs. Legend has it that canines are born with psychic abilities, and when they bark at the air, they are, in fact, warning off the unseen. On one hand, they can see “beyond the veil,” and on the other, they appear to emerge unscathed from each such encounter. Upon this observation, the Chinese built a reputation around dogs for being able to defeat evil.

Early in imperial China, there were already written records of dogs used in sacrificial rites against misfortune. For one, in the great history Records of the Grand Historian (史記; Shǐ Jì), the First Emperor (秦始皇; Qín Shǐ Huáng) had dogs killed at gates for said purpose. Similarly, Fēngsú Tōngyì (風俗通義), the book of customs, speaks of people painting white dogs’ blood on doors and windows. An alternate version claims that the blood of black dogs works even better as their pelts render them invisible to supernatural threats in the night—plus, the battle god Èrláng (二郎神) himself is accompanied by a mythical black dog. Today, sacrificing your pooch is, of course, unthinkable, but clinically taken blood still occasionally has a place in ceremonies and exorcisms alongside living dogs. Dogs, it would seem, are man’s best friend in more ways than one.

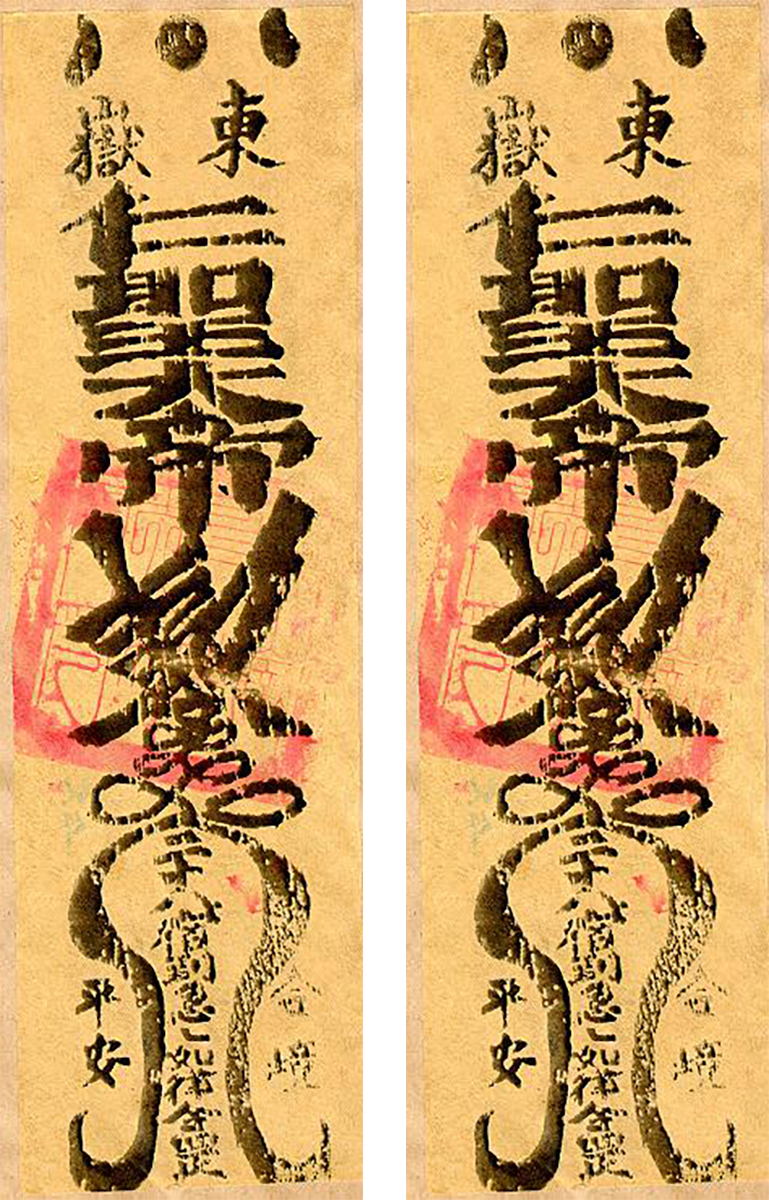

Found on Chinese vampires’ foreheads, coffins, and the doors of forbidden haunted abodes, the fú (符) is perhaps the most represented Chinese tool against ghosts and monsters. This paper talisman has its roots in early Chinese shamanism and sorcery, and through the ages, it has been adopted into Taoist practice. In its common form, it is a sheet of yellow paper on which sets of characters are inscribed in cinnabar.

Unsurprisingly, the composition of the fú is carefully considered. Yellow, in the Chinese cosmology of a world balanced between metal, wood, water, fire, and earth, corresponds to the central earth. The talisman’s paper is therefore of a prime colour that reigns over all, including the supernatural. Red is accordingly a lucky colour in Chinese culture, and more importantly, cinnabar is an earth-nurtured mineral that has long been applied when sealing ancient tombs. Paper, “ink,” and Taoist characters of the fú, then, are all selected or designed with warding in mind, and so they are used. Whether put up or burnt, even downed with water as ashes, it remains a favourite protective essential.

Water, of course, has no literal roots; it is simply named as such in Journey to the West (西遊記; Xī Yóu Jì) because it has no source to trace to in seas, rivers, or wells. Caught as it falls from the heavens, rain before it touches the ground is deemed the purest water there is. The fact that rootless water is untainted by either the earth or that which is secular sets it apart as a polar opposite of and a remedy to the “filth”—as the Chinese see it—that are ghosts and monsters. Primarily, rootless water was valued for its medicinal use in ancient China; in more obscure corners, the Chinese use it to cleanse the body of not just diseases, but also evil influences. In a sense, it is not unlike Dorothy’s bucket in The Wizard of Oz.

Tales on the power of peach wood are many. In one, the archer Hòu Yì (后羿) was murdered with a staff crafted of peach wood. For his heroics, he ascended to godhood as lord over all ghosts, but the peach wood he lost his life to subsequently became something all his subjects steer clear of. In another version in Fēngsú Tōngyì, it was under a peach tree that the divine brothers Shén Shū (神荼) and Yù Lǜ (郁壘) surveyed ghosts and executed punishments. As a result, all ghosts developed an aversion for peach wood, and the Chinese took to carving the brothers’ likeness on the wood to put in homes as wards. Always high on the Chinese list of materials to use against ghosts, peach wood is usually wielded by Taoist priests as swords, though other products such as charms also abound.

In the West, the willow is associated with death. So, too, is it in China, albeit in a quite different way. The Buddhist Consecration Sutra tells of a willow tree under the care of a monastic order whose branches can cleanse the inflicted of evil influences when dipped in water. The goddess Guān Yīn (觀音) is known for her vase of willow branches, which she employs to put a stop to dark threats. The agricultural classic, Qímín Yàoshù (齊民要術), advocates planting these same branches at front doors to bar ghosts from entering. With its roots dug into superstitious beliefs, the title “ghosts’ bane” follows every ordinary willow and its branches. Perhaps oblivious to its origins, we continue planting willow branches at every Qing Ming Festival, one of the Chinese festivals of the dead. The branches serve on silently to be worthy of their title.

Sometimes you need to look no further than your kitchen for the supernatural weapon of your dreams. From Taoist priests showering beans on the ground for them to take shape as legions, to practitioners of the occult arts offering beans to those who wish to prevent illnesses, the humble legume has doubled as a key ingredient in Chinese endeavours against ghosts and monsters. One possible origin for this is a myth concerning the water god Gòng Gōng (共工) and his wayward son. Committed to villainy, in the afterlife, he was no longer divine, but a ghost of pestilence. His peculiar fear of red beans, like Hòu Yì’s of peach wood, spread among his fellow ghosts—making bean porridge on Winter Solstice is a popular traditional dish, said to mark the date of his death and protect the Chinese from his kind.

Mirror, mirror on the wall, who’s the scariest of them all? The “mirror of monsters” is prevalent in every other Chinese folktale on the supernatural—none except the old and very experienced can escape these surfaces that see right through their monstrous souls. Whatever deceiving illusions they put up, monsters have nowhere to hide in reflections, and little makes them shudder more than exposure. On top of revealing monsters’ true forms, mirrors are mentioned in relation to feng shui in the herbology volume Compendium of Materia Medica (本草綱目; Bén Cǎo Gāng Mù). Combining the essence of metal and water, Chinese copper mirrors are dull on the outside with a brightness within to tap into. Keep one over your heart, wisdom says, if not on your wall.

Chinese ghosts knew to fear spit way before the age of COVID-19. In the famous Chinese ghost story, “Song Dingbo the Ghostseller” (宋定伯捉鬼; Sòng Dìng Bó Zhuō Guǐ), the titular hero ran into a ghost on the road to the market. The brave young man tricked the ghost into believing him a new ghost who was ignorant of their ways. Not long after, the hero turned the newly gained knowledge right back on the ghost once they arrived at their destination—his spit on the ghost made its temporary disguise as a goat permanent. Some say this is because spit is so filthy and toxic, exceeding that which the Chinese believe ghosts to be. What we can be sure of is that our predecessors were wary enough of spit to firmly describe it as a substance ghosts fear above even the Taoist fú.

Top