By Localiiz

Branded | 17 May 2024

By Localiiz

Branded | 14 May 2024

Copyright © 2025 LOCALIIZ | All rights reserved

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to get our top stories delivered straight to your inbox.

Header images courtesy of Ryan Moulton and Danielle Barnes (via Unsplash)

Originally published by Catharina Cheung. Last updated by Charlotte Ip.

As can be expected from a civilisation with a long-standing history, Chinese mythology is far from monolithic and is the result of the integration and absorption of nearby cultures from different historical periods. Chinese folklore, legends, and stories are an amalgamation of ideas from Han Chinese culture, the Han predecessors known as Huaxia, Manchurian culture, Tibetan faith and mythology, Korean mythology, and many others besides.

Much of mythology revolves around exciting tales of heroic archetypes, villains, deities, and supernatural beings, designed to promulgate religious ideas or cultural values. While some such characters have become famous enough to have transcended cultural boundaries—many in the western world have heard of Sun Wukong the Monkey King (孫悟空), and the goddess of the moon Chang’e (嫦娥), for example—there are plenty of other less humanoid creatures just as important to Chinese culture, but whose stories are lesser-known to those outside East Asian cultural circles. Here are a non-definitive round-up of Chinese mythical creatures and supernatural beings that are interesting to know about.

Possibly the most ubiquitous of all Chinese mythological creatures, the dragon has long been a revered symbol of power and luck. While typically stylised as powerful but also aggressive and rather malicious in European culture, Chinese and East Asian dragons are seen as highly auspicious, bringing about luck, windfall, and harmony. You won’t find St George being praised or canonised in Asia for slaying a dragon!

In imperial China, the only person allowed to use and wear motifs of this creature was the emperor, and thus, the dragon has always been used as a symbol of the royal family. While imperial family members like princes were also allowed to bear this symbol on their robes and accessories, they would use a four-clawed dragon, while the mightier five-clawed dragon was reserved solely for the emperor. When China created its first national flag during the Qing dynasty, it was only natural that its main feature was a dragon. In colonial Hong Kong, a semblance of this cultural relevance was represented in the use of a dragon as part of the city’s coat of arms while under British rule.

Chinese dragons also differ from European dragons in that they are depicted as long and snake-like, with no wings. This is also the style in which the Japanese depict their dragons, but just speak to a tattoo artist well-versed in Asian culture and design, and they will tell you the easiest way to tell between them is to look at their feet—Chinese dragons are usually drawn with five claws, while Japanese dragons have three.

According to the earliest-surviving Chinese dictionary Erya (爾雅) from the third century, this mythical bird has the beak of a rooster, the face of a swallow, the forehead of a fowl, the neck of a snake, the breast of a goose, the back of a tortoise, the hindquarters of a stag, and the tail of a fish. Most depictions are not quite as detailed, and mostly show a multicoloured pheasant-like bird with long tail feathers like a peacock.

Male phoenixes were originally called “鳳” (fung6) and the females were called “凰” (wong4), but this gender distinction is often no longer made, and all phoenixes are collectively known as “鳳凰” (fung6 wong4). A mostly feminine entity, phoenixes are the polar opposite to dragons, which are generally seen as masculine.

Symbolising high virtue and grace, the phoenix was used exclusively in imperial households by the empress. The combined motif of dragon and phoenix symbolises the union of yin and yang and is therefore often seen in marriage ceremonies. Male and female fraternal twins are also referred to in Chinese as 龍鳳胎 (lung4 fung6 toi1; “dragon and phoenix infants”).

Although its origins are unclear, the nian is a mythical beast that plays one of the key characters in the Lunar New Year. Legend has it that at the beginning of every year, the nian would come out of its lair to feed on men and animals in nearby villages. Some stories describe it as a creature like a flat-faced lion with a dog’s body and large incisors, while others say it is a huge beast with two long horns and sharp teeth.

In a bid to drive the nian away from their homes, the villagers discovered that the beast has a fear of fire, loud noises, and the colour red. Villagers then decked out their homes in red decorations, lit fires, clashed gongs and cymbals, and set off loud firecrackers—traditions that we have retained in Lunar New Year celebrations to this day. In fact, the enduring presence of the nian in Chinese culture is also the reason why we refer to the Lunar New Year holiday as “過年” (gwo3 nin4)—to “pass over the nian.”

This odd mythical creature is a hooved chimaera whose appearance is said to signal the imminent arrival or passing of a sage or an illustrious ruler. Qilins are thought to be divine, peace-loving creatures, only appearing in areas ruled over by wise and benevolent leaders. It was first mentioned in text in the fifth-century literary commentary Zuo Zhuan (左傳) and is later mostly associated with the giraffe.

Some Chinese explorers supposedly made a voyage to East Africa during the Ming dynasty, bringing back many exotic animals to China, including giraffes. The emperor was convinced that their capture was a sign of his great power and might, and named the giraffe the qilin. This theory is supported by the description of the qilin as being a quiet herbivore, with the ability to “walk on grass without disturbing it,” antlers like a deer, and scales like a dragon—qualities that may also artfully describe a giraffe’s long, thin legs, horn-like ossicones, and tessellated pattern on its coat. This identification of giraffes with the qilin has had lasting influences: in Korean and Japanese, the same word is still used for both the long-necked animal and the mythical creature.

Because the qilin has a single horn, it is often translated into English as a “Chinese unicorn,” though this can be misleading as they are very different beasts and, in any case, some qilin may also be depicted as having two horns.

Another hybrid, chimerical creature, the pixiu is mostly depicted as a stocky, winged lion. In more detail, they have the head of a Chinese dragon, the body of a lion, and will have either one or two antlers on their head. Males have one antler and are said to bring wealth home to its master, as well as guard the money already at home; females, also known as bìxié, are identified by two antlers and will ward off evil.

Pixiu are said to be auspicious and can attract wealth towards themselves, though this is likely because it is also described as having a voracious appetite for gold, silver, and precious stones. It is also said that pixiu do not have anuses, meaning they will ingest money and wealth without later passing it out. For these qualities, this is a mythical creature popularly used in the art of feng shui—pixiu decorations placed around the home, office, or as small accessories on your person are said to bring wealth and prosperity.

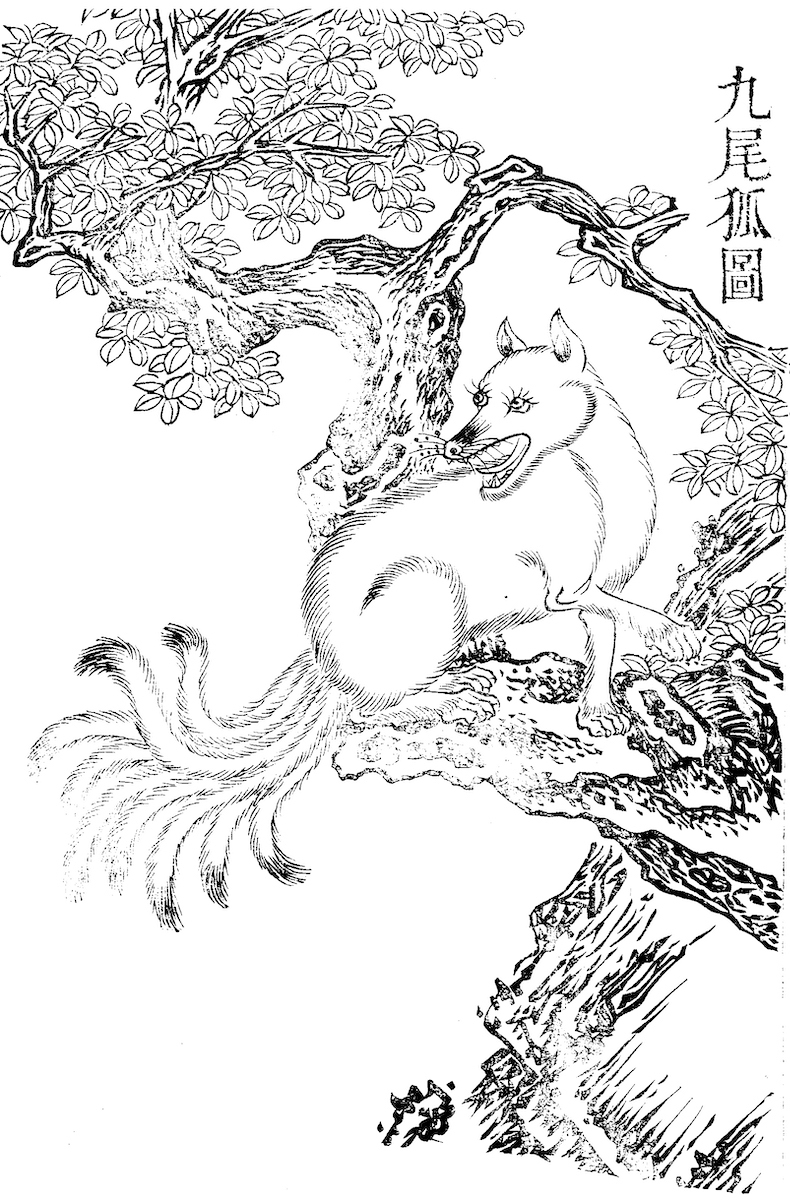

Not every mythical creature has positive connotations. The fox spirit is a common character in East Asian folklore, appearing in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean cultures. Mostly depicted as mischievous shape-shifters, the fox spirit often appears in tales disguised as a beautiful woman, usually attempting to seduce men for their own entertainment or to eventually feed on them. This is why in today’s Chinese culture, a woman who actively attracts and seduces lots of partners is scornfully called a “狐狸精” (wu4 lei4 zing1; fox spirit).

The nine-tailed variety of the fox spirit appeared in the Classic of Mountains and Seas (山海經; saan1 hoi2 ging1), an ancient text from the Warring States era written by Yu the Great. Although described as an eater of mankind, the text does also state that it is an auspicious omen that appears during times of peace and that eating a nine-tailed fox will protect a man from being poisoned by insects. This is also a creature that has been associated with divinity; the nine-tailed fox is sometimes depicted alongside the goddess of immortality Xi Wangmu (西王母), or being present at Mount Kunlun (崑崙), the mythical divine mountain range.

The Chinese notion of a vampire is different to the blood-sucking, coffin-dwelling, garlic-fearing Western variety. Although commonly referred to in English as vampires, Chinese vampires are more akin to zombies—its Chinese name literally means “stiff corpse.” Vampires are often depicted as grey-green bodies dressed in official garments from the Qing dynasty that get around by hopping with their arms outstretched in front. Instead of feasting on fresh blood, they kill living creatures to absorb their qi life force.

Ideas as to why a dead person might end up becoming a vampire vary from source to source, but some causes include the use of supernatural acts such as voodoo to resurrect the dead, a body not being buried after the funeral, when a pregnant or black cat leaps across the coffin, or when there is an inherent clash in good and evil within a person’s soul and the good portion departs for the afterlife while the bad part remains and reanimates the dead body.

A supposed origin for vampire tales comes from the folk practice of transporting a corpse over long distances when a loved one passes away far from home. As legend has it, poor people who could not afford to have their dearly departed transported back to them could hire a Taoist priest to reanimate the body and have it “hop” their way home.

These priests would operate only at night, ringing bells to alert people in the vicinity as it is considered bad luck for the living to lay eyes on a vampire. Taoist paper talismans might also be stuck to a vampire’s forehead to immobilise it as and when needed by the priests, a feature that is still present in popular depictions of vampires in films and drawings to this day.

Traditional Chinese architectural styles always feature doors with a bottom jamb or raised threshold approximately 15 centimetres in height; it is typically said that this is to prevent vampires from being able to enter households because they can only hop, and cannot lift their legs high enough to climb over the threshold.

Unlike Greco-Roman myths where the Oracle of Delphi is the sole master of prophecy, Chinese folklore makes available a sizable team of clairvoyants besides the well-known qilin. Able to herald the rise and fall of a benevolent ruler, the zouyu is said to resemble royalty in many ways, too. On the outside, it is gifted with a lion’s head, a tiger’s body, and a five-coloured long tail, and the mythical creature is entrusted with the power to oversee terrestrial beasts. On the inside, the carnivore is believed to have immense self-discipline, as it neither steps foot on grass nor feeds on preys of unnatural passing.

Given the mythical leader’s exemplary character, it is often cited as a role model for prospective sovereigns and even commoners alike. Rites of Zhou (周禮; zau1 lai5), a bureaucracy commentary, is amongst the many scriptures that advise its readers to emulate the zouyu’s benign nature and cease hunting down living beings.

When in doubt, consult the baize—at least, this is what ancient Chinese says. Manuscripts from the Song (960–1279), Ming (1368–1644), and Qing (1636–1912) dynasties all claimed that the baize is all-knowing and well-versed in the human tongue, making it an expert in warding off evil spirits or ill fate. Legends say that the baize manifested before the Yellow Emperor and divulged secrets of 11,520 monsters at large, who then instructed his men to take notes, which later became the prized antique book Báizé Tú (白澤圖). Part of the baize’s wisdom is still alive on shelves of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and the British Library.

Literature from the Yuan (1271–1368) and Ming (1368–1644) dynasties described the creature as possessing dragon-like features (some say the head, others say the body). In the Tang (618–907) dynasty, the belief in the baize’s powers to exorcise demons garnered an incredible following. Vulnerable families began embroidering the mythical creature on pillows or nailing the Báizé Tú on doors in a bid to cast away misfortune.

Perched outside the Court of Final Appeal, the statue of Lady Justice—blindfolded and clutching a scale and sword—is famously inspired by the Roman goddess of justice, Justitia, embracing values that the local law system holds dear. However, the Chinese have their own interpretation of the celebrated concept, albeit in a less humanoid shape.

Known as the xiezhi, this mythical beast is portrayed as either an azure-skinned goat or mountain cattle with a horn protruding from the skull. Said to possess the foresight to tell right from wrong, this discerning creature is a well-trusted arbitrator in disputes and never shies away from impaling and biting the irrational party.

Although the xiezhi draws numerous parallels to judges in court, it was not officially endorsed as a figure of justice until the Spring and Autumn period (770–476 BC). It is said that King Wen of Chu (楚文王) crafted a “xiezhi crown” (獬豸冠) in hopes of paying homage to the creature. All of his commands were graciously welcomed by the state, and the headpiece endured as a definitive item of clothing for imperial judges for dynasties to come.

No, this creature is not one of your myopic friends—in fact, it reportedly has clearer sight than many for having two eyeballs on each side! According to the Taoist treatise of Shi Yi Ji (拾遺記), the four-eyed bird has the appearance of a rooster and the crook of a phoenix. For such a domestic façade, however, the winged species is deceptively feisty and said to be helpful in ousting ferocious wolves and tigers that ravaged towns.

Legends say that the fabled beast first entered Chinese territory as a tribute to the fictional Emperor Yao (堯) and soon made a name for itself by driving out malicious forces. Yet, the creature only visited sporadically and was far from able to keep all threats at bay. In a desperate attempt to safeguard lives and property, the villagers carved wooden roosters and installed them on doors and on rooftops. Much to their delight, the aggressive mammals that had plagued them did not appear since. Roosters, who were celebrated as being the doppelgänger of this legendary bird, would also go down in history as an animal of auspice.

As a hybrid of two supreme celestial guardians, the dragon turtle’s grandeur is self-evident. A folktale recounted that the dragon-headed, turtle-bodied breed is one of the prestigious nine sons of the dragon (龍之九子), who goes by the name of Bixi (贔屓) or Baxia (霸下). Other versions suggest that the dragon turtle spawned from an intertribal marital affair or is an alternate realisation of the black tortoise (玄武), a shelled creature entangled by a snake.

Regardless, the dragon turtle lucked out on all of its positive connotations, embodying not only the dragon’s fortune and authority, but also the turtle’s longevity, guardianship, and health. To top it all off, the creature’s name (in Mandarin) is a homonym of “honourable return” (榮歸), rendering it a popular ornament to enhance feng shui in homes and offices alike. Often depicted sitting on a bed of gold or protecting monumental sites, the beloved crossbreed is said to impart great fortune to those who can touch its shell.

We can all agree that the stone lions outside of the HSBC Main Building are iconic landmarks, but did you know that they have roots embedded in myth? Surprisingly, historical versions of the sculpture barely resemble the “king of the jungle” at all. Some stories claim that lions were delivered to ancient China during the Western Han period (202 BC–9 AD) but this is often dismissed as nothing more than rumours. Eventually, the mellow Pekingese dog was what sculptors reportedly settled on as a reference.

Later, when Buddhism took ancient China by storm, the guardian lion gradually became more important, and the dog-like statue inherited the legends surrounding the religious character. It is likely that Buddhism furthered the guardian lion’s role as a protector, and Chinese elements have been imparted to them. In line with the yin-yang concept (陰陽), guardian lions always appear in pairs, featuring a male on the left pressing on a Japanese temari (てまり) and a female on the right enveloping a cub. As a pair, they are believed to cast a protective shield upon the premise. From royal tombs and palaces to upscale residences, the Chinese guardian lions stand as unchallenged assets for outstanding feng shui.

Top